The winners of the NZ Institute of Architects' Auckland Architecture Awards were announced last night. There's a whole host of great buildings here. We'll start with the houses.

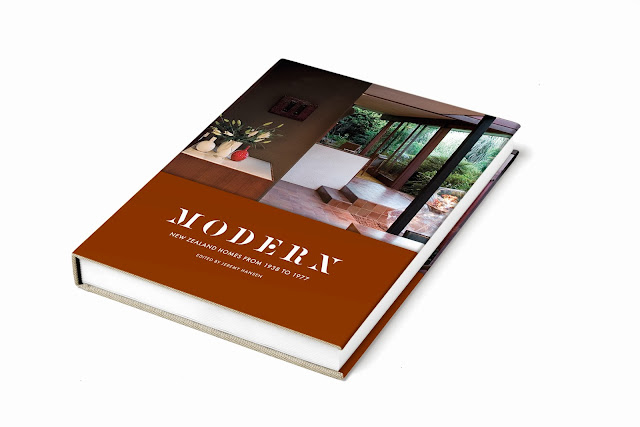

The Newcombe House in Parnell, Auckland (below) was designed by Peter Bartlett and won an Enduring Architecture award. You can see this terrific house published in full in our new book, Modern: New Zealand Homes from 1938 to 1977, which is in bookstores on November 1. The photograph is by Samuel Hartnett.

The other winner in the Enduring Architecture category was the Yock House (below), designed by architect Lillian Chrystall.

In the Housing category, RTA Studio won an award for the Stable Lane apartments (below), which featured in our June/July issue. The photograph is by Patrick Reynolds.

New York-based, New Zealand-born architect David Howell won a Housing Award for this home on Auckland's Upper Queen Street (below), photographed by Patrick Reynolds.

Glamuzina Paterson Architects picked up a Housing award for this holiday home on Waiheke Island (below), photographed by Samuel Hartnett.

Strachan Group Architects designed the Nikau House in Parnell, which also won an award in the Housing category (below). It also won a Sustainable Architecture award. Photograph by Jackie Meiring.

You might remember this from our February/March issue last year: the Ngunguru House (below) by Tennent + Brown Architects, another winner in the Housing and Sustainability categories. Photograph by Paul McCredie.

Strachan Group Architects also picked up Housing and Sustainability awards for their work for VisionWest Community Housing, two low-budget homes in West Auckland (below). Photograph by Jackie Meiring.

The Takapuna House by Athfield Architects (below) is on the cover of our current issue, and also won a Housing award. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

On Waiheke Island, the Macalister House (below) by architect Wendy Shacklock picked up a Housing award. Photograph by Patrick Reynolds. Watch out for this in one of our upcoming issues.

This home (below) by Dorrington Architects also won a Housing award. Photograph by Emma-Jane Hetherington.

Another Housing award winner to watch out for in an upcoming issue: the Tarrant/Millar house in Point Chevalier (below), designed by architect Guy Tarrant (who also happens to have a home in our current issue). Photograph by Patrick Reynolds.

The Cliff Top House (below) by Xsite Architects featured in our August/September issue last year, and also won a Housing Award. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Patterson Associates won a Housing award for this home (below) in St Mary's Bay, which you can also look forward to seeing more of in one of our upcoming issues. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

And the final award in the Housing category went to the Dune House (below) by Fearon Hay Architects, photographed by Patrick Reynolds.

Onwards! Now to the Interior Architecture category, in which there were five winners. The first, the St Heliers Bay Bistro (below), by McKinney Windeatt Architects. Photograph by David Straight.

Jasmax won an Interior Architecture award for their work on AUT's Sir Paul Reeves Building (below), which also won an award in the Education category. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Cheshire Architects garnered an Interior Architecture award for their work on Milse (below) in Auckland's Britomart precinct. Photograph by Jeremy Toth.

The York Street Mechanics cafe (below) in Parnell, with an interior by Bureaux Architects, was another winner in the Interior Architecture category. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett.

And the final Interior Architecture award went to CPRW Fisher for the Lincoln Road fitout (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Onto the Heritage category, where there were two winners. The Fox Street Office (below) was designed by Fearon Hay Architects and photographed by Jackie Meiring.

The other winner in the Heritage category was Salmond Reed Architects for the Allendale House and Annex on Ponsonby Road (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Now Commercial Architecture, in which there were four winners. McKinney Windeatt Architects won an award in this category for their design of the Special Building, just behind Victoria Park Market (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Also in the Commercial Architecture category, Warren & Mahoney won an award for their work on the renovation of the ANZ Centre in Albert Street (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

RTA Studio won a Commercial Architecture award for the McKelvie Street shopping Precinct (below), which you might remember from our February/March issue. Photograph by Patrick Reynolds.

And the final Commercial Architecture award went to Jasmax for the Quad 5 office building at Auckland Airport (below), which also won a Sustainable Architecture Award. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

To the Education category, in which RTA Studio won an award for the St Kentigern College MacFarlan Centre (below). Photograph by Patrick Reynolds.

Warren & Mahoney won an Education award for the Massey University Albany Student Amenities Centre (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Kay and Keys Architects won an Education category award for the Unitec Marae Stage 2 Wharekai (Manaaki) (below), photographed by Greg Kempthorne.

Warren & Mahoney won another award in the Education category for the University of Auckland University Hall. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

In the Public Architecture category, Archoffice won an award for the refurbishment of the ASB Theatre at the Aotea Centre (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Warren & Mahoney won a Public Architecture Award for the Point Resolution Footbridge (below), just beside Auckland's Parnell Baths. Photograph by Patrick Reynolds.

Jasmax won a Public Architecture award for the Muriwai Surf Lifesaving Club (below). Photograph by Kenneth Li.

Also in Public Architecture, Glamuzina Paterson Architects and Hamish Monk Architect won an award for the Giraffe House (below) at the Auckland Zoo. Photograph by Mark Smith.

In the Small Project Architecture category, Archoffice won an award for this Auckland Council Amenities building (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Also winning a Small Project Award is the Arruba Bach by Bossley Architects (below), which you should look out for in an upcoming issue of HOME. Photograph by Simon Devitt.

The House of Steel and Light (below) by Robin O'Donnell Architects also won a Small Project award. Photograph by Fraser Newman.

BVN Donovan Hill and Jasmax won an award in the Sustainable Architecture category for ASB North Wharf (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Finally, the Planning and Urban Design category, in which Sills Van Bohemen won an award for Takapuna's Hurstmere Green (below). Photograph by Simon Devitt.

Construkt Architects and Isthmus Group won a Planning and Urban Design Award for the Sunderland Precinct comprehensive development plan in Auckland's Hobsonville Point (it's not developed yet, so there's no photo).

And the final winner in this epic post is Matter and Auckland Transport, who designed this temporary installation on a disused part of Spaghetti Junction motorway to raise awareness of cycling. It won a Planning and Urban Design award. Photograph by Alex Wallace and Laura Forest.

.jpg)